INTRODUCTION

Helene Brandt was stronger than steel.

As she bent welded steel tubing to create her sculptures, so Brandt shaped the difficult material of her early years, transforming it with the force of her humor and courage. Though she struggled throughout her life with the shadows of her mother’s depression and a series of family tragedies, she incorporated that dark emotional weight in powerfully honest and witty pieces that she formed around her own body, pieces expressing the pain and vulnerability, the fiercely joyful resilience, and the assertive loyalty to her own independence that she experienced as a woman.

A combination of architectural lucidity and id-like impulse, her work strikingly explores – with irony, whimsy, passion and ferocious intelligence – the vanishing lines between self and surroundings, protection and entrapment, stasis and motion, the heaviness of suffering and the sheer, dancelike freedom of willed flight.

“So much emphasis was placed on creativity when I was growing up that I tried to rebel against it,” wrote Brandt, whose father was an engineer and whose mother was a sculptor in clay. “But I wasn’t successful in overcoming my strong need to understand my father’s logic in an emotional way and my mother’s emotions in a logical way. … Nature, invention, art, rationality and irrationality are all part of my background and part of my art.”

In welded steel, Brandt wrote both the text and subtext of an adventure that she populated with versions of herself and of us, versions she – and we – could literally put on and walk in like costumes. Carapaces, winged creatures, powerful giants, the fragile and the young in need of shelter, inhabitable monsters – all of their simple strength and their complicated fears and joys revealed as much through space and suggestion as through mass. A world of dark outlines is what she created, absent of solid corpus at the center, yet invisibly fleshed with intention and feeling in every dimension, all alive and all human, somehow. Perhaps even superhuman.

“When performed through interaction, Brandt’s works become fantastic hybrids, both animate and inanimate, human and machine,” wrote Matthew Friday in notes for Brandt’s 2003 show at State University of New York/Oswego. “These cyborg prosthetics lend our bodies new attributes and describe a system of unique and potentially infinite anatomies and interactions; in essence, they are sites of possible being and becoming.”

Brandt was constantly, determinedly, becoming. Along the way from her childhood in Philadelphia to her last years as a highly regarded and extensively shown New York artist, she wed at 18 and raised two sons; went to college at 29 and earned successive degrees from the City University of New York, Columbia University School of the Arts and St. Martin’s School of Art; received awards including a Guggenheim Fellowship, a National Endowment for the Arts Artist-in-Residence Grant and the Betty Brazil Memorial Award; lived and worked in England, Denmark and Italy; saw her work exhibited and acquired in eight nations on four continents; taught at 12 different New York-area institutions; and sustained a 59-year marriage with her husband, Philip Brandt.

What Brandt lived and what she synthesized from that life have resulted in artwork of highly personal form and content – the creations of a human being with the imagination of an inventor, the wit and passion of a choreographer, and the perspective of a unique woman at a specific place and time in the history of the world. “Her work has many roots,” noted Michael Brenson in a 1984 New York Times review. And, he added, “a touch of Leonardo.”

IMAGES

Click image to scroll. Clink link in image to goto related works.

Note: All Helene Brandt artwork images posted at www.helenebrandt.com are downloadable, but may not be used for publication unless fully credited as Courtesy of the Estate of Helene Brandt and, where provided, the photographer’s name.

IN HER OWN WORDS

I didn't start out in sculpture. My first love in the arts was dance and my favorite activity was improvisation. I completely lost myself in the world created by my moving body. But there were things I didn't like about it. I couldn't stand back and look at what I was doing. Everything disappeared when I stopped moving. Except for the pure physical joy of dancing, making sculpture satisfies me more. I can be more inventive with form and when I stop working, the sculptures continue to exist and what I learned and experienced as a dancer has been incorporated into my sculpture. My artistic decisions are both visual and visceral.

– Helene Brandt, Columbia University School of the Arts website, 2008

Link to full copy in Web Archive

Chaos and order, complexity and simplicity, stillness and movement. The search to understand it all through my sculptures just leaves me awestruck.

– Helene Brandt, from the brochure for “Three Sculptors,” 2001, Bernice Steinbaum Gallery, Miami, Florida

“Path of Expanding Vision” is both a meditative space for introspection and a pathway that leads through different doorways that metaphorically express varied and ever broadening ways of looking at the world. A student resting on the arms joining the three portals becomes part of the sculpture. Some of my most pleasurable memories are from my travels through Southern Italy and Greece, of the contemplative time spent resting against the columns of Greek temples and gazing out at the surroundings which they frame.

– Helene Brandt, from promotional brochure for “Paths of Vision: Works by Helene Brandt,” 1995, The Gallery of Contemporary Art, Sacred Heart University, Fairfield, Connecticut

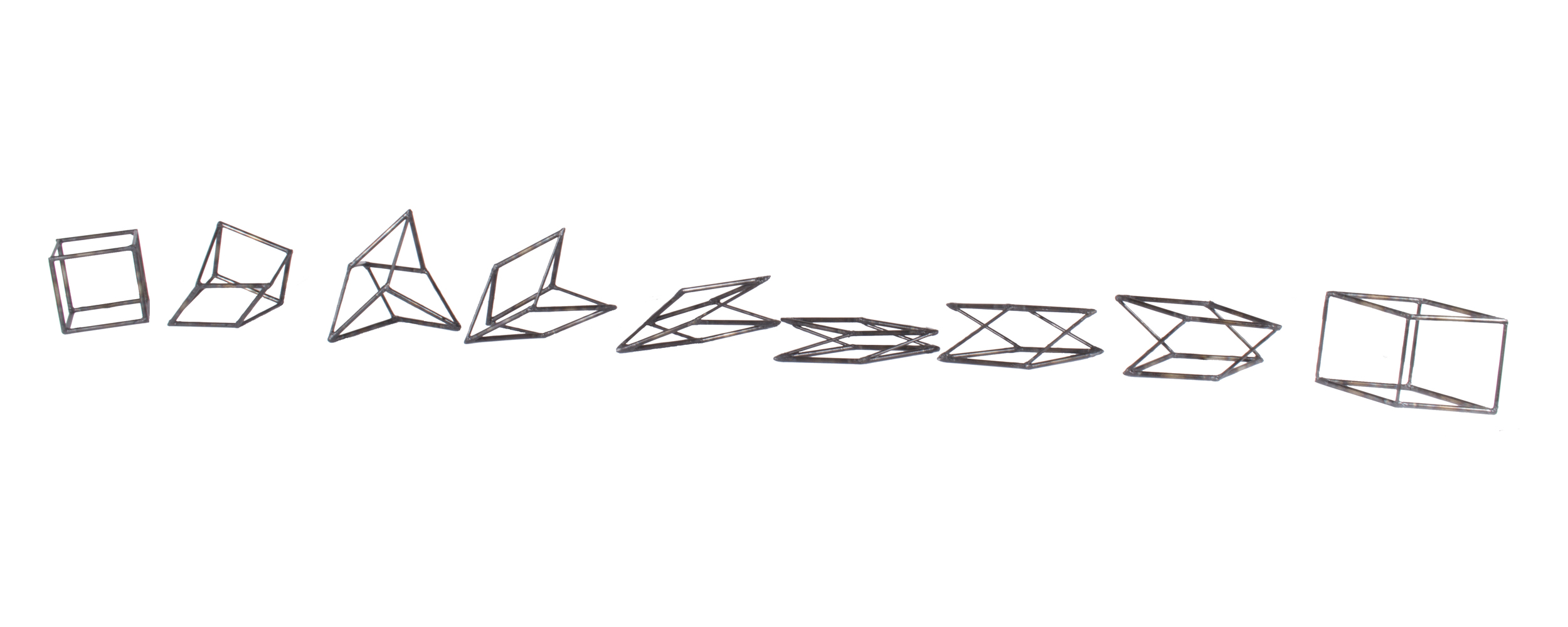

In my work, I express my fascination at living in a three-dimensional world. Any object you look at changes as you or it moves in space. A simple chair is exciting. If you walk around it and draw it from ten different angles, you will get ten different shapes. My sculptures are like stop-motion photography brought into the third dimension. The players are abstract objects that continue to change as you move around them. You can look at them one at a time, or you can look at them all together as elements of a larger architectural whole.

– Helene Brandt, from the catalogue for the “Parameters” series, 1994-1995; Trinkett Clark, curator, The Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk Virginia

COMMENTARY

These works make thoroughly ambiguous the separation between the natural space and the movement of the body and that of the machine. When performed through interaction, Brandt’s works become fantastic hybrids, both human and machine, animate and inanimate. These cyborg prosthetics lend our bodies new attributes and describe a system of unique and potentially infinite anatomies and interactions; in essence, they are sites of possible being and becoming.

– Matthew Friday, Assistant Professor of Art, from the brochure for “The Sculpture of Helene Brandt, Body Enclosures 1998-2003, Mondrian Variations, 1995-1996,” Tyler Art Gallery, State University of New York at Oswego

In her earlier works such as Cradle, Brandt constructed safe havens into which one could retreat. In this exhibition, the sanctuaries are not only safe havens, they now allow for the inhabitant to leave with the assurance that the sanctuary will be there should return be necessary. Surrounded by the steel leaves of Crocus, one can, like a bud, wait crouched inside for the perfect time – the first moment of spring or the awakening of the soul – to open and bloom.

– from the promotional card for “Helene Brandt, Open Sanctuaries: New Work,” 1999, Steinbaum Krauss Gallery, New York City

Helene Brandt’s newest work stands as an affirmation of the genius of Mondrian. It also reasserts her conviction that making art is not about the final product, but rather about the journey toward discovery.… Shifting In and Out of the Third Dimension features Brandt’s most recent Mondrian Constructions alongside of her earlier Cage Sculpture. This juxtaposition begs us to consider what has been called the “great divide” between two of the most influential movements of the early twentieth century: Constructivism and Surrealism. Climbing into these earlier steel tube cages – often equipped with wheels or rockers – our experience of three dimensional space is hampered by the unforgiving rigidity of grid barriers. Yet these harsh and hollow environments beckon human interaction for the sake of their completion, for the sake of other truths.

– Lois Fichner-Rathus, PhD., from the brochure for “Shifting In and Out of the Third Dimension,” Mondrian Variations and Cage Sculptures, 1996, Steinbaum Krauss Gallery, New York City

Brandt’s motive is explicit: she is interested in discovering and encapsulating the hidden impulse that triggers the nucleus of movement. This passion is evident in both her welded steel sculptures and her graphite drawings, where she investigates the shadows her forms create. Through her exploration of kinetic force, Brandt is able to capture the essence of energy, motion, rhythm and balance as she examines a simple, abstract shape – such as a cube – and its kaleidoscopic potential.

– from the catalogue for the “Parameters” series, 1994-1995; Trinkett Clark, curator, The Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk Virginia

She has a great appreciation for learning and maintains a sense of wonder as she conducts explorations of line, space and form in welded-steel sculpture and graphite drawings. The work embodies many contrasts – forms that sit still and yet have so much to say about movement, cool elegance shaped by a fiery torch, serious inquiry and a great sense of playfulness, rich complexity and equally rich simplicity.

– Barbara Hatfield, from promotional brochure for “Joyfully Realized: Steel Sculpture by Helene Brandt,” 1994, Memorial Union Gallery, North Dakota State University

Helene Brandt transforms steel into a sequence of metamorphosing structures. Her architectonic evolutions in sculpture and drawing are a relationship of the organic to the geometric. They borrow from the vocabulary of architecture and engineering and anatomy. ….Brandt brings her training as a dancer to these sculptures that appear to be choreographed in steel in a celebration of movement. The process of transformation whether physical or metaphysical is visionary and it shares a lyricism with dance.

– from promotional card for “Archectonic Evolutions: Sculpture and Drawing,” 1993, Steinbaum Krauss Gallery, New York City

Each of the sculptures is a composite of five to fourteen component pieces, charting evolutions of a particular form. Brandt uses steel rods to construct elegant and powerful drawings in space. Her work has evolved over the years from cage-like enclosures built around her own body to airy three-legged pieces that suggest movement, to this new work which is an exploration of movement itself…. Each work embodies a progression that is an abstract parallel to Muybridge’s serial studies of human and animal actions.

– from promotional card for “Progessions: Sculpture and Drawings 1989-91,” The Bernice Steinbaum Gallery, New York City

LINKS TO ARTICLES

Sculptor Helene Brandt uses discarded, found, and organic objects to create a symbiotic universe in the throes of change. Steel, wood, roots, wire, leaves, paint, varnish, and vegetation all meld and focus our attention on the revelatory characteristics of each object. …There is an acute sense that each sculpture could move at any instant and exchange parts with the next to create a new entity. …The tension between clinging to the familiar and fearing the unknown facilitates constant movement. This adaptive universe is always “in progress” and like all good symbiotic relationships, the members depend on each other for survival and reinvention.

– from the exhibition essay for “Helene Brandt Adaptations: The fragility and fierceness of metamorphosis,” 2012, curated by Deborah Johnstone, Metro Center Gallery, New York City

Visitors should also experience "Progressions and Processions," a show of welded pieces by Helene Brandt. Using steel rods of varying thicknesses, Ms. Brandt bends them into angular and curved shapes, then parks them in lines on low bases. One is a procession of molar-like shapes all the same size; another is a progression that begins with a cube and ends with a cube flattened. They are small, precise and engaging, and they come with related charcoal drawings.

– Vivian Raynor, "ART; In Various Guises, the Human Form Endures as Inspiration", The New York Times, 1991

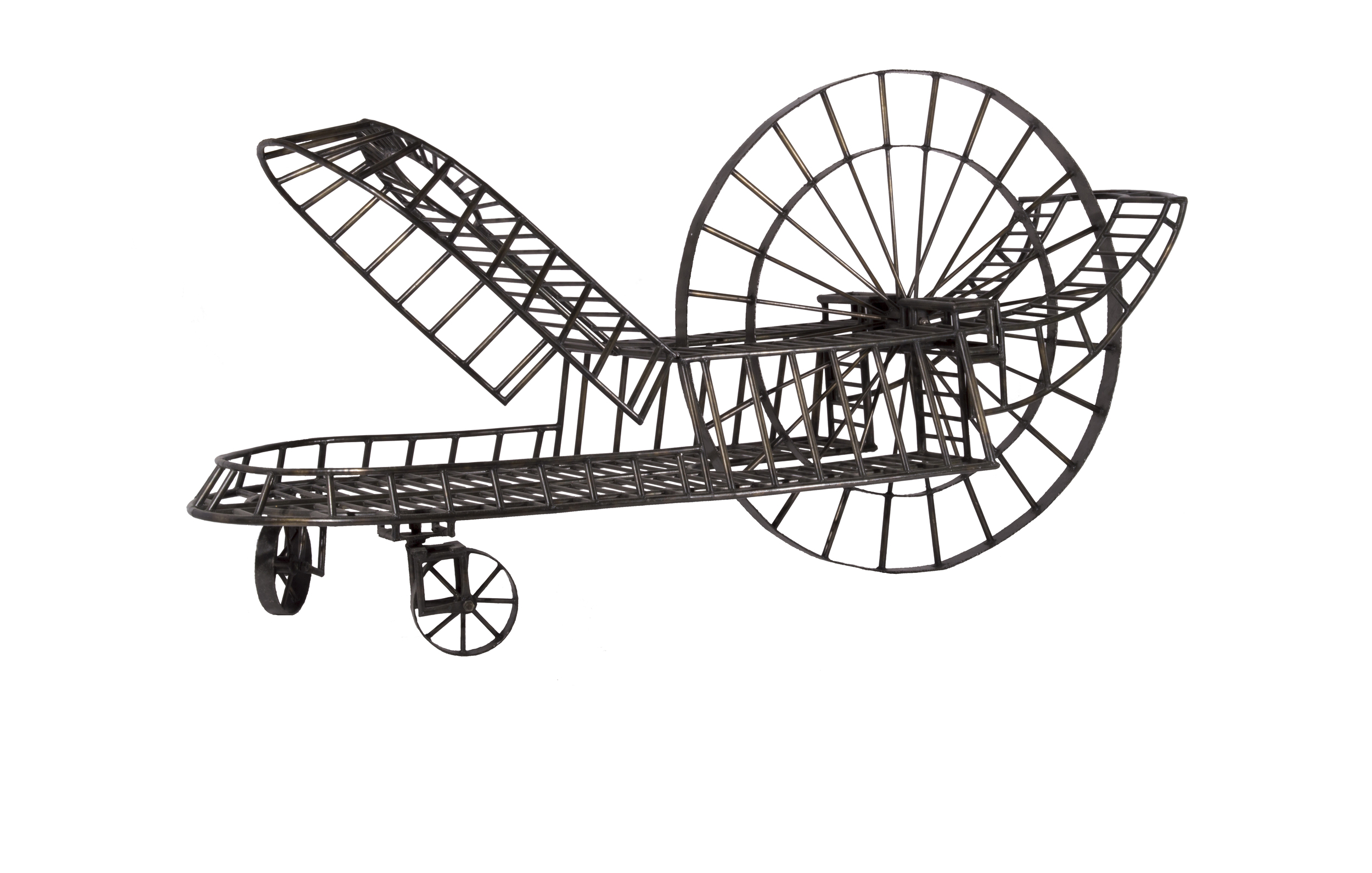

Brandt’s sculptures hint at themes of strength and vulnerability, inspiration and alienation, freedom and restraint. To address these dualities, she derives her imagery in part from the animal world. Ornithopter is at once a bird and a cage. From a distance, it appears to be a squawking predator, ready to attack. On closer inspection, the animal becomes a human cage in which the viewer may actually sit. The sensuous steel curves promise protection, enticing you to curl up inside. But the uncomfortable steel seat and close fitting steel bars confine and trap.

– Anne Classen, "Helene Brandt: Sculpture and Drawings", INLIQUID art + design, 1987

“The Throne” is a skeletal box that invites us to enter and sit down. The huge, oversize light bulb above us lets us know that we are in an enchanted think box. The light that lets us know when we get an idea is always on. Ideas are guaranteed. But the box is also like a prison cell for someone in solitary confinement, in which the light is never turned off. In other works by Brandt as well, protection and danger, inspiration and solitude go together.

– Michael Brenson, "ART: Welded Sculptures By Helene Brandt", The New York Times, April 6, 1984

The fact is that animal imagery is providing something of an antidote to mainstream art. This past year brought to New York the stumpy lions and stuffy vultures of painter Earl Staley, the affectionately chiseled sheep in the paintings of Louisa Matthiasdottir, the creaturely plants of Nancy Graves, the carapacial contraptions of Helene Brandt, the sculptural performing troupe of Zigi Ben-Haim, the ceiling-tall demonic wood creatures of James Surls and the bounding and bewildered deer, tigers and monkeys of Melissa Miller.

– Michael Brenson,"GALLERY VIEW; Animals Creep Back Into Today's Art", The New York Times, June 24, 1984